Recognition

1999 AIGA Medal

Born

1945, Decatur, Illinois

By Lorraine Wild

September 3, 1999

Follow Us

I have to begin this essay with a confession: it is not easy to write about an old friend and teacher, someone to whom I owe so much. I have been in awe of Katherine McCoy's talents and accomplishments for the almost thirty years that I have known her, and that admiration is framed by my experience of being her student at Cranbrook back in the '70s. When I heard that Katherine McCoy was being awarded the AlGA Gold Medal, I interpreted it as a sign that the AlGA was honoring design education through this specific award to such a consummate educator. My reaction may be an automatic reflection of the stubborn split between those designers who perceive themselves primarily as educators, and those who see themselves primarily as professionals. And I am sure there are designers out there who think Katherine McCoy comes purely from the educator's side, and is somehow detached from the pragmatic concerns of day-to-day practice. But what I wish to describe is how the work of Katherine McCoy has been concentrated in education, and yet has had an enormous impact on design practice in the United States during the last two decades, and conversely, how the professional work and activities that she has engaged in have also functioned as educational, and have made a terrific contribution to the maturing of design in the broadest sense.

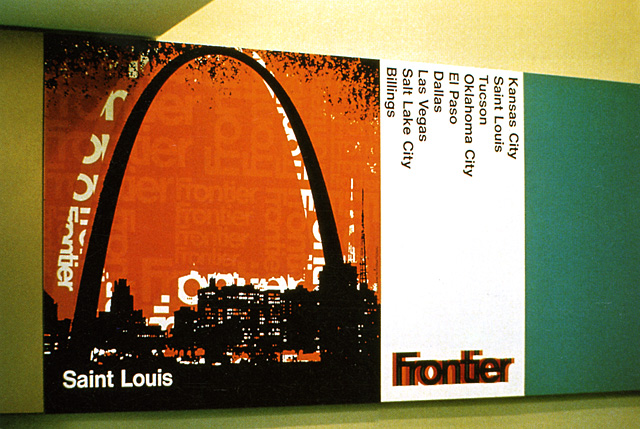

Katherine often has said that it was a visit to the Museum of Modern Art (on a family trip to the New York world's Fair in 1964) that made her realize she was most interested in the power of design. After majoring in industrial design at Michigan State University and graduating in 1967, she took a job in the Detroit offices of Unimark International, design consultants who produced some of the largest and most notable corporate identity projects of the period. The offices of Unimark, where she received her real typographic training, were famous for the strict, clean “Swiss” Modernism of their designs, which at that time was still unique, almost exotic to corporate communications. Not only did Unimark sell their work to their clients, they also promoted a hyper-rational problem-solving approach to corporate communications, detached from advertising or marketing. The house journal, Dot Zero, published some of the earliest arguments in the United States in support of the Modern style. Immersed in the ideology of problem solving through “objectivity” in form, she spent hours poring over the office copies of the “Swiss Bibles,” typographic books by Müller-Brockmann, Ruder, Gerstner, and Hofmann.

(top left) McCoy and McCoy symbol, 1995; (top right) Cranbrook Crane symbol, Cranbrook Educational Community, 1994; (bottom) Cranbrook logotype, Cranbrook Educational Community, 1994.

7Up Cans (green and red) from the collection of Tim Samuelson. Photograph: James Prinz Photography, Chicago.

Tivoli, 1977. Photography: Thomas B. Wendell.

Her experience at Unimark was followed by a year at Chrysler Corporation's corporate identity office, and then by a Boston office, Omnigraphics, that consulted with Muriel Cooper at the MIT Press, which provided further opportunity to hone the typographic approach she had developed at Unimark, and a design office in Detroit, Designers and Partners, which was quite a different place altogether. Designers and Partners was oriented toward working with advertising agencies, mostly on automotive accounts, and had a staff that consisted of all sorts of graphic arts “professionals,” including illustrators, cartoonists, and “lettering men” as well as graphic designers. Although she did not particularly enjoy the work with advertising clients (finding the focus on selling to be contrary to her interests in communication), Katherine was exposed to a very lively group—including her colleague Edward Fella, who was later to become one of the more influential participants (as both a critic and a graduate) in the Cranbrook design department, and whose aesthetic was as eclectic as Unimark's was pure.

In 1971, Katherine and her husband, Michael, an industrial designer, were founding their partnership, McCoy & McCoy Associates, when they were asked by the Cranbrook Academy of Art to become co-chairs of the design department. Under the direction of Eliel Saarinen from the '30s to the '50s, Cranbrook's graduate-level design department had nurtured and produced several students who went on to become major forces in American architecture and design—Harry Bertoia, Eero Saarinen, Florence Schust (Knoll), and Ray and Charles Eames, among others. But all schools go through cycles and not much had happened in design at Cranbrook after that. After some hesitation, Michael and Katherine accepted the position, walking into a department that had a great past but no present—although it did have the incredible and subtly beautiful Saarinen-designed campus as a daily reminder of what could be accomplished in that place.

The McCoys were free to reinvent the programs in 2-D and 3-D design however they wanted. Katherine recalls that she combined the “objective” typographic approach that she knew through professional practice with an interest in the social and cultural activism that was in the air in the late '60s. One early recruitment poster for the program features text that describes the goals of the design program in almost completely Utopian terms, combined with a collage that reproduces fragments of provocative design from both the professional and avant-garde design traditions of the twentieth century. The beginning of the McCoys' program at Cranbrook can be seen as part of a wave of activity in U.S. design programs that was directed toward more high-level experimental work. California Institute of the Arts, the Kansas City Art Institute, and the Rhode Island School of Design, among other schools, started to offer alternatives to the graduate program at Yale, one of the advanced programs in graphic design studies that not only trained people for professional practice, but encouraged them to work speculatively, beyond the professional model.

The tensions and contradictions between the Modernist obsession with process and methodology versus the fascinations with both historical and speculative form were always in play at Cranbrook. Katherine McCoy describes her role as a “parade organizer” or a “coach,” concerned with setting the scene for a rich interchange between students. The remarkable thing about Cranbrook under the direction of the McCoys that is not well understood is how, on the surface, a department with so little structure actually worked. The art school was run without classes, grades, requirements, or deadlines other than a final thesis show, and yet the place was a beehive of activity. This has lots of anecdotal explanations—winter weather so bad that there was nothing to do but work, or haunted dorm rooms—but the truth as usual is more complex. The McCoys had a good eye for the right students, and really knew how to create an interesting mix of personalities in the studio. After a brief foray into interdisciplinary projects, the students were segregated into projects but not into separate studios, so graphic designers were exposed on a daily basis to the problems of industrial designers, and vice versa. Students sat in on one another's critiques without regard to specialty. It is true that Katherine leaned on her Modernist typographic background at the beginning (I remember Kathy handed me a copy of Ruari McLean's translation of Jan Tschichold's Asymmetric Typography and said, “Here, read this, it's all you really have to know about type.”) but she soon evolved a short sequence of introductory projects for the graphic design majors that would accelerate their progress from standard typographic skills into the ability to play more fluidly and expressively with typography.

Over the years Katherine designed a lot of material for the Cranbrook educational community, quarterly magazines, catalogues, and posters, along with other projects that she and Michael produced as McCoy & McCoy. Within the tradition of the atelier there were many opportunities for students to collaborate with Katherine on the design of works that were actually realized. This is the counterbalance to the experimental work of the Cranbrook students, which was so often reproduced yet not understood to be part of a wider range of projects undertaken in the department. However, that interest in process and progress that the McCoys had brought to the program transformed itself into an obsession with the possibilities of change and transformation of design practice itself. At the studios and the critiques at Cranbrook, discussions often centered on the possibility of breaking away from the norms of everyday practice. Katherine and Michael required the students to read about both historical and contemporary design and theory, to really understand the context in which each student was going to be entering. In retrospect, this might have seemed a bit presumptuous for a design department in a somewhat obscure art school in the northwestern suburbs of Detroit, but the internal expectation set up by Katherine and Michael was simply that they (the McCoys and the students) were in this not only to make interesting work, but to make their mark upon the development of the field. And Katherine's ongoing work outside of Cranbrook, with its orientation toward public education, such as the Design Michigan project of 1977, the Colorado Native American Heritage poster project of 1978, or the Fluxus book of 1981 constantly set the example of work that worked, both formally and conceptually, for its audience.

Cranbrook Design: The New Discourse, Rizzoli International, 1991, on 10 years of Cranbrook student, faculty, and alumni design work.

Supplier Communications Manual, 1968. Designed while working as staff designer at the Chrysler Corporation Identity Office.

Bicentennial jazz concert series, Cranbrook Academy of Art Museum, 1976.

Design Michigan educational posters 1 and 3, 1977, conceived, written, and designed by a faculty/student team including Katherine and Michael McCoy and Cranbrook design department graduate students.

Something else that Katherine and Michael McCoy gave their students—although it was obviously never taught, it was offered purely by example—was the idea of living a life that could not be divided simplistically between life and work, but that integrated life and love and design and work absolutely seamlessly. The McCoys, like all the Cranbrook faculty, lived and worked on campus, although they were the only teachers who worked as a team, as a creative partnership, and as a married couple. Every day the students witnessed what prodigious things could be accomplished under such an arrangement! The power and positive energy implicit in the creative partnership of McCoy & McCoy (that simple equation, one plus one) proved to be exponential, and again only emphasized the importance of commitment both inside and outside of the design studio.

Katherine took two leaps in the design of the design program during the late '70s, which led to its second, very influential phase. First, she began to alter the introductory typography projects to allow a semiotic interpretation to begin to drive the solutions, and she allowed the students to depart from the stricter Modernist vocabulary of previous years, to include stylistic elements that had previously been underused by Modernist typographers, such as historical or vernacular type forms or images. The second leap was to let the students, who were more than ready and able, to take the lead on the exploration of theory, but to insist that it always be resolved as a visual problem rather than an academic one. This again emanated from Katherine's honest assessment that the strength of the Cranbrook tradition was one of making meaning through making real work. Also, what cannot be underestimated is Katherine McCoy's ability to put together classes of students who would challenge without competitively destroying each other, and her ability to articulate an ethic of community that somehow encouraged this high level of productivity. It is important to note that while Katherine was running the 2-D program at Cranbrook and consulting on myriad design projects, she also served as the first woman president of the Industrial Design Society of America (1983–1985), sat on the national advisory board of the AlGA, and chaired the Design Arts Fellowship Grant Panel for the National Endowment for the Arts for three years. The generous amount of time she spent on the development of professional organizations during these years of growth came out of her conviction that it constituted an extension of her teaching time—that the organizations were critical to the ongoing development of the design itself. She has a holistic view of the interrelationship between the academies and the design offices, and sees the professional organizations as the natural link, a force for education that does not stop with school.

Another aspect of Katherine's influence has been her writing, which has always been cogent, jargon free, and clear in its commitment to the continuing education of all designers, not just those in school. After she and Mike took a sabbatical in Holland, she wrote an essay in I.D. Magazine titled “Reconstructing Dutch Graphics” (1985), which was one of the first explorations of the new Dutch work to appear in an American design magazine. It did a lot to draw the attention of young American designers to the high level of contemporary design being produced there and helped to instigate many exchanges between American and Dutch graphic designers during the next few years. But most of Katherine's writing has been focused on issues specific to education or to attitudes that affect design practice, inside and outside of the classroom. A continual theme running through her writing is that of authenticity an ethics: in education (working through ideas about understanding the criteria to judge effective programs to teach design) and in professional practice (exploring the idea of commitment to social and cultural and political activity and the tension between that an. the stubborn notion of the disengaged professional). Also, she has used writing to spur her own research into the articulation of new ideas in design, and in the process has often found the words to explain what we are experiencing visually at that moment. That writing, which would include her essays on typography and now on new media, has entered the syllabi of studio and seminar courses in design schools across the country.

In 1991, the McCoys (with a large team of 2-D and 3-D students) produced the book Cranbrook Design: The New Discourse (Rizzoli International Publications). The book documented the high-octane visuals of the work that had been produced in the Cranbrook studios during the 1980s, and it probably sealed the reputation of the school as being a place where the visual quality of the work, sometimes generated by a highly creative (or even mistaken!) interpretation of theory took precedent without regard to the “needs” of the profession. Again, the critique that often met the work represented in that book was often voiced without knowledge of the actual discourse of the studio critique, driven by the McCoys, that challenged the experimentation to be as real as possible, out of a dedication to realizing the Utopian ideal of design that informed, delighted, and somehow liberated its users.

The McCoys gave up their chairmanship at Cranbrook in 1995 after sustaining twenty-four years of coherent and energetic work. They moved to Chicago, where they spend every fall semester as senior lecturers at the Illinois Institute of Technology's Institute of Design. Katherine in particular has somewhat moved away from studio teaching, and has instead been concentrating more on theoretical issues having to do with both the teaching and practice of graphic design in the context of new media. In fact, this has brought her back to issues of design methodology, information and communications theory and the audience, not far from where she started both under the influence of Unimark and the late '60s obsession with process over form. Like many other educators facing the shift in technologies brought on by design for electronic media and the web, Katherine recognizes that we are facing a profound shift that cannot be answered with the same set of principles that framed the backbone of the last several decades of design for print. But she does bring a depth of experience and perspective to this new challenge (and, again, phenomenal energy for study and research). She initiated and chaired the American Center for Design's “Living Surfaces” conference in 1992, the first U.S. design conference on the subject of new media, and has written many articles and lectures devoted to this new phase of her ongoing work.

Katherine and Michael spend the rest of the year in the mountains of Colorado, in what, from afar, looks like semi-retirement. But up close the image shifts completely: in their totally wired encampment they continue their projects and their research. Even the teaching doesn't really stop—this year Katherine and Michael have launched “High Ground,” a series of studio charette workshops open to professional designers in their studios. Katherine has often advised younger designers that they must regard the design of their own careers as a project itself, and that they must choose their paths carefully. Even in that remote location, the path that Katherine has taken, and continues to take, integrating life and art and design and work, resonates in the work of so many others from coast to coast. It is for work accomplished, but an exemplary process still in progress, that this AlGA Gold Medal seems most appropriate.

First published in 1999 by AIGA.

Keep in Touch with AIGA

Sign up for email communications to be the first for updates on webinars, events, programs, and announcements.