Recognition

2007 AIGA Medal

Born

1959, Sudbury, Ontario

By Thomas de Monchaux

September 19, 2007

Follow Us

It was a dark and stormy night, in the figurative sense. A sleepless Bruce Mau, having decided that he had ruined what was, at that point, the second most important job of his career, phoned his client across five time zones from Toronto to Paris, to confess. “Michel,” he said, “I've just done a terrible thing.”

The client was Michel Feher, editor of Zone Books, and the year was 1989. The project was Zone 3/4/5: Fragments for a History of the Human Body, the series that followed Mau's most important job to date—1985's Zone 1/2: The Contemporary City, a complex compendium of critical thinking about urbanism from philosophers such as Gilles Deleuze and Paul Virilio, architects Rem Koolhaas and Christopher Alexander, and edited by Feher and Sanford Kwinter. “That book was the breakthrough; it set the tone for everything that followed,” says Mau, who founded Bruce Mau Design studio that same year. Featuring graphic elements such as densely saturated landscapes of color and textured images, landmarked by bold figure-ground moments of typographic punch and void, that tome would become the first in a series of epochal—and very big—books.

Kwinter recalls, “In those—pre-computer—days I was working with half a dozen designers trying to work up a program that broke with the sterile rationalism of post-1960s design—in the same way as did the philosophers and artists that we were wishing to publish. Mau at first had no idea what I was talking about, but his first maquette for Zone 1/2 had more ideas in it than some other designers' entire careers.”

Mau aimed “to do an object that wasn't an illustration of the content, but a model—something that performed and behaved like the city itself. As if you're holding the city in your hands and experiencing the city through the book over time.” It marked the beginning of a body of work that would become “a map of . . . public time and space,” as the Village Voice said in its review of Zone 1/2 at the time.

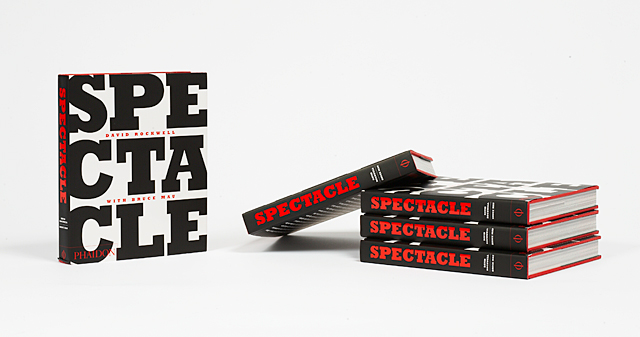

Spectacle, by David Rockwell with Bruce Mau, 2005-2006 (Image: Bruce Mau Design Inc.).

But designing Zone 3/4/5 proved problematic—specifically, the covers. Mau's rich, colorful details of enlarged paintings had looked so brilliant on the light box, but now, fresh off the presses, seemed a muddy mess. “We just didn't have time to remake the film or anything else—we'd already manufactured our own inks, our own paper,” says Mau. With the clock ticking away, “we realized we could just reassign ink colors to different plates on the press: red, blue and purple, to get a different kind of complexity. I called Michel. I threw away the truckload we'd already printed. I started over. It was a huge success.” The lesson, Mau says, was about, “being willing to allow creative work to keep going past the usual boundary, after everything had already been settled.”

The inspiration for changing plates—for making changes, whether small or massive, and for not settling—goes back to the very beginning of the printing process and to the start of Mau's own education. Born in 1959, Mau grew up in northern Ontario. “I thought I was going to be a scientist. I like to say I didn't hear the word 'design' until I went to art school,” he says. His introduction to art education was a yearlong program in Special Arts at Sudbury Secondary School. Mau's first assignment had little to do with design. “I had to restore and refurbish a one-color offset press,” an already vintage, 12 x 18 sheet-size Heidelberg. “You'd be surprised at how difficult that is,” he says. And he had to make four-color prints on the one-color press. “For every color, every time, I had to take it apart and put it back together.”

That taste for unconventional processes led Mau to the Ontario College of Art and Design, where he studied advertising under Terry Isles. Before graduating, he joined Toronto design firm Fifty Fingers, and two years later moved to Pentagram in London, where he worked with David Hillman and Herman Lelie. It was at Pentagram, in turbulent Thatcher-era Britain, “that I was really introduced to the political life of form,” says Mau. He was also introduced to the virtues of deeply interdisciplinary practice, how graphics could participate in other systems. “I learned that people like [Lelie], for example, had whole other lives as artists, and collaborators like John Cage,” he says, “[and] how design and culture converge around literacy, equity, society.” Mau brought that lesson back to Canada, where he co-founded the design practice Public Good Design and Communications before splitting off to form Bruce Mau Design. There, finally, is where he would balance print design work—for Zone Books and I.D. magazine, for which he served as creative director in the early 1990s—with more boundless pursuits.

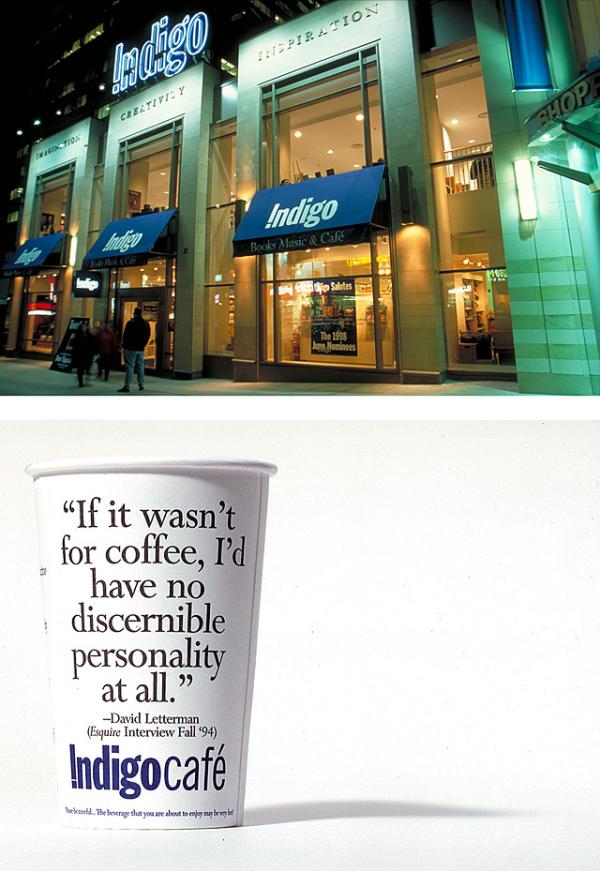

Museum of Modern Art banner for Kohn Pederson Fox, 2000-2004 (Image: Bruce Mau Design Inc.).

Mau's studio has worked especially closely with architectural practice—both through environmental graphics and wayfinding systems as at Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, as well as through collaborative monograph and documentation projects such as 1996's mammoth S,M,L,XL, the 1,376-page blockbuster prospectus for Rem Koolhaas's Office for Metropolitan Architecture. “That really was a turning point,” says Mau. “Rem insisted that I become an author.” As a result, “people recognized that the design itself was actually a critical work, and was itself content.” He recalls, “This was the first of what I call 'context projects,' articulating the changing context within which design is located,” he says. In 2000, Mau's own monograph, Life Style, advanced that agenda.

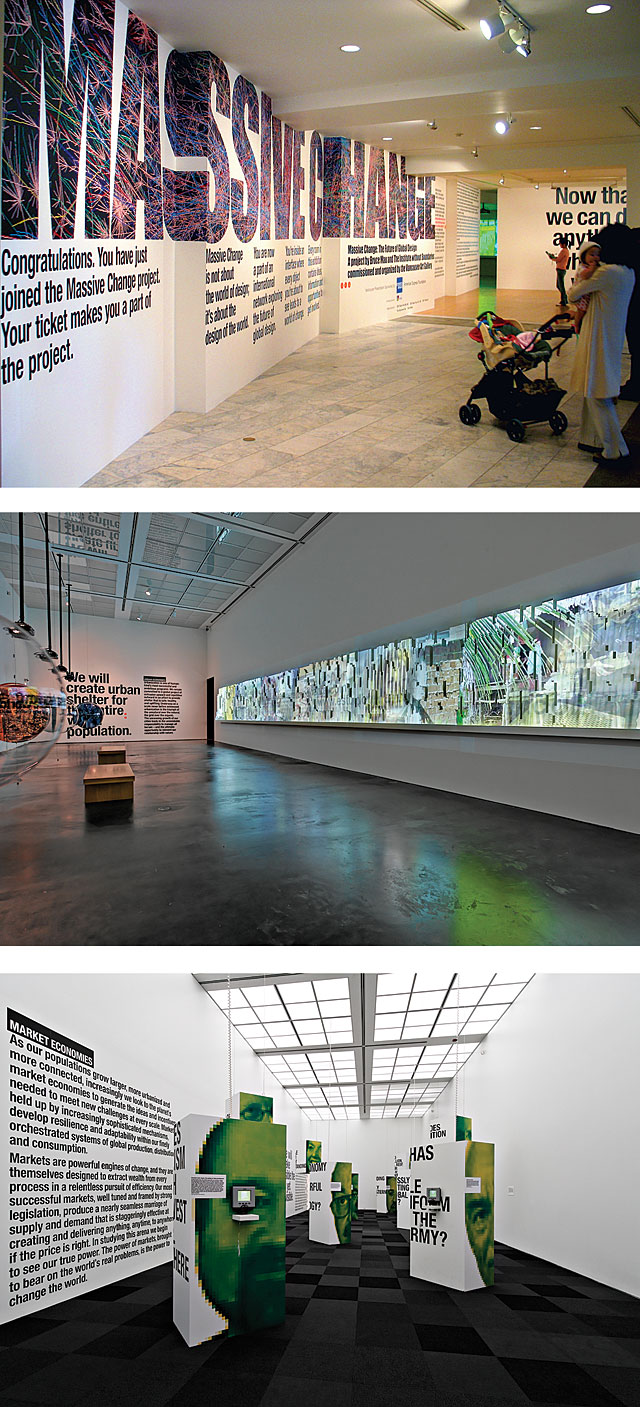

Other context projects include Tree City, set in Toronto's Downsview Park, which recontextualized urban-scale design work within graphic practice. (Mau and collaborators Koolhaas, David Oleson and Petra Blaisse won a 2001 competition to create that landscape, and Bruce Mau Design now oversees its 10-year development.) And “Massive Change: The Future of Global Design”—originally a 2004 exhibit at the Vancouver Art Gallery but now a book, website and an ongoing initiative with the stated goal of “exploring the legacy and potential, the promise and power of design in improving the welfare of humanity”—is the culmination of such interdisciplinary thinking. With its visionary approach to ecology, economy and everything in between, the project relies on research by students at the Institute without Boundaries, a post-graduate, interdisciplinary design program that Bruce Mau Design developed in 2003 with George Brown-Toronto City College, and is now also associated with the Art Institute of Chicago, a city in which Mau's practice is increasingly based.

Mau's idea for “Massive Change” was to talk to 100 technicians and thinkers, craftspeople and laypeople who were changing the world, whether they knew it or not. “They're all designers according to us,” he says. “Some of them didn't think they were designers, but they use the word 'design' more intelligently, colloquially, than we do as designers ourselves.” With work transcending traditional professional boundaries, “they just blew all those categories away,” he continues. The outcome is “design simply as a critical methodology for solving problems.” That's the approach of those whom Mau cites as powerfully pairing visual discourse with big ideas, as well as the ambition to bend or mend the world. Eames, Nelson, McLuhan, Duchamp, Hamilton, Fuller, he proffers.

But does Mau aspire to join that list? “Nah,” he demurs. “Well, maybe late at night.”