Recognition

2009 AIGA Medal

Born

1935, Cuba

Deceased

2018, Sedona, Arizona

By Holly Willis

March 1, 2009

Follow Us

Recognized for introducing narrative and nonlinear dimensions to design for films, changing our visual expectations and demonstrating the power of design to enhance storytelling.

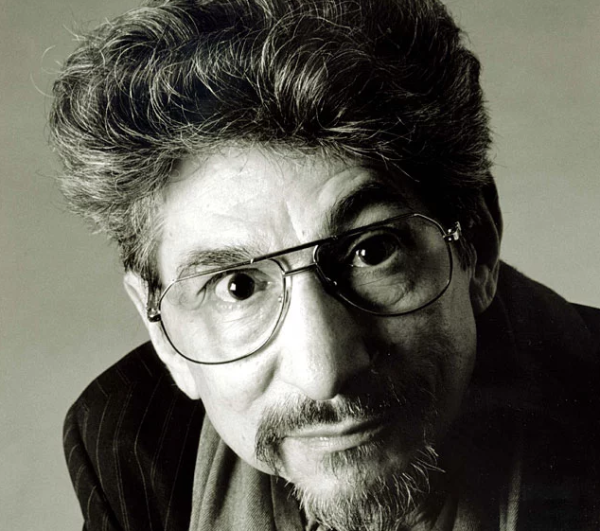

“Keep it moving,” says the 74-year-old, Cuban-born, Los Angeles-based designer Pablo Ferro, who cuts a dashing figure with his wild hair, large-rimmed glasses and trademark red scarf. The prolific title designer, whose body of work includes the groundbreaking openers for films as varied as Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Hal Ashby's Being There (1979) and Gus Van Sant's To Die For (1995), is synthesizing the key to his aesthetic. Ferro's designs captivate through kinetic urgency, drawing viewers into, around, through and over dynamic, graphic landscapes that do a lot of work: introducing a film's credits, setting the stage for the story to come and underlining the fact that motion pictures are about nothing if not motion. “Everything I do is always moving,” he says, adding that the movement emerges organically because he frequently listens to music while he works. “Music helps me edit,” he says. “It helps me cut—my mind just works that way. It works in a tempo, and when I cut, it's always with rhythms.

Those rhythms have accentuated Ferro's work for nearly 50 years. Ferro, who left Antilla, Cuba, with his family at age 12 and grew up in New York City, taught himself animation based on his love for Disney films. He worked as a comic-book artist and animator in the 1950s, formed a production company called Ferro, Mogubgub and Schwartz in 1961, and then started his own company, Pablo Ferro Films, in 1964, using the short format of the TV commercial as a means for practicing a new, powerful form of visual communication.

In 1963, Ferro was invited by Stanley Kubrick to create the sequence that would reverberate throughout the industry: the titles for Dr. Strangelove. Ferro was working on the trailer for the film when he and Kubrick began talking. ”He asked me a question about human beings at one point,“ says Ferro, ”and I told him, 'Everything we do is always very sexual.' A B-52 refueling in midair? Of course! It's sexual.“ Ferro reports that one of the surprising results of his first title sequence was not merely international acclaim but the opportunity to work on other provocative sequences. ”They said if I could make planes sexual, I could make anything sexual,“ he laughs.

Inspiration for the motion and rhythm that make Ferro's work so remarkable sometimes came from unlikely sources. In describing the notorious polo scene in Norman Jewison's The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), Ferro cites popular styles of design in print as his model. ”I was very influenced by magazines at that time,“ he explains. ”I'd look at magazines and see a bunch of pictures on a page, and I thought, 'That's beautiful. If I could ever get that into a movie, it would be amazing.' But it's impossible. You have a few minutes to look at a page, but in a movie you only have a few seconds to look at something.“ Despite his reservations, Ferro began experimenting. ”What I did was try to design the images so that your eye would go in a certain direction the whole time. I wasn't just making multiple pictures, but leading your eye through the pictures.“

In The Thomas Crown Affair, the polo sequence splinters into dozens of rectangular images, each containing fragments of the story in motion, sometimes falling into a grid resembling the Eadweard Muybridge motion studies from the turn of the last century, and at other times showing close-up details of a larger segment also onscreen. The sequence is visually dynamic—and stylistically breathtaking in its control and economy—but most of all, the split screen brilliantly captures the essence of what is now an everyday vernacular: the ability to view dozens of images simultaneously and select and organize them, or the visual language of the database. Long before the existence of Flickr and Final Cut Pro, Ferro mapped the possibilities of the edited sequence across the screen in a kinetic, nonlinear way, using a method now commonly referred to as ”database narrative,“ in which the emphasis falls not on linear storytelling but on the processes of selection and combination. Intuitively, Ferro understood data's dynamic potential.

Perhaps the other chief characteristic of Ferro's work is his perspicacious understanding of the power of metaphor. His work may be first and foremost visual and vibrant, but it's also narratively pertinent. Take his concept for the title sequence for Secretary (2002)—drawn from titles Ferro designed in the 1970s for an obscure black-and-white video he made called The Secretary. Steven Shainberg's Secretary opens on a typewriter ball as it spins frenetically and clacks out letters. Then there is a pause as we read the names of the actors. This pattern of diligent activity and repose captures the movie through the interplay of pleasure and work that the film centers on. Similarly, in the title sequence for To Die For, the camera glides in tight on a series of newspaper images, moving so close that the images devolve into halftone dots as Ferro manipulates the figural and the abstract, and the fine line between knowing something and then not knowing it.

Several critics have said that Ferro was one of the first artists to recognize the significance of typography in crafting effective title sequences. He used unusual type choices in his commercials, and in his title sequences, he invariably finds a means to communicate story, character and themes through typography. Indeed, Ferro's hand-drawn titles—the tall, gangly letters drawn with a slightly shaky hand—are instantly recognizable. These, too, started early in his career, helping give Dr. Strangelove its continued power. But why hand-drawn titles for that film? ”When we showed the first titles, Kubrick said he didn't like them,“ recalls Ferro. ”He didn't know whether to look at the lettering or at the plane. And I said, 'You have to do them both at the same time,' but the only way you can do that is if you make the lettering very big and thin, you know? And there's a lettering I always did for myself, and I used that to draw the titles and we did the test with the lettering and the images at the same time, and he loved it.“

Ferro's career has spanned dramatic changes in visual culture, filmmaking and technology. Films are now cut at a frenetic pace, and cameras are more mobile than ever, creating a sense of intense visual immersion that makes it hard for viewers to look away. The frames-within-frames aesthetic that made The Thomas Crown Affair a masterpiece is now common, seen in TV shows such as 24 and in innumerable commercials. Similarly Ferro's notion of mixing forms—uniting hand-drawn titles with narrative imagery, or using music as a means to think visually—are all now part of a convergent culture, as software allows live-action images, animation, music, drawings, photographs, print-based graphic design and more to coalesce in the same format, and then function in synergy. However, Ferro understood the power of this dynamic, inclusive language as early as the 1960s, when his commercials mixed wildly divergent materials and used quick cutting and a moving camera to keep viewers glued to the screen.

Ferro still produces, directs and designs, sometimes working with his son Allen Ferro, and he also continues to consult with other directors on tricky scenes and sequences. He has been recognized widely for his contributions to film and design, receiving the Chrysler Design Award, the Art Directors Club Hall of Fame Award and now the AIGA Medal, and he is the subject of a forthcoming documentary directed by Richard Goldgewicht, which will chronicle Ferro's remarkable career.

Asked how he retains his edge through several decades, Ferro laughs and says, ”I never show my tricks. I try not to show how something was done, to make it seem as if it came naturally or that it wasn't worked on.“ And, of course, he lives by his other key motto: ”Keep it moving.“