2019 AIGA Medalist: Alexander Girard

Recognized for his effortless ability to move across innumerable surfaces and scales, his life-long innovative and inspirational cross-disciplinary design practice, and his undeniable impact on mid-century modernism in America.

Recognition

2019 AIGA Medal

Born

1903

Deceased

1997

By Kelsey Keith

March 25, 2019

Follow Us

Alexander Girard was a designer who defied easy categorization, mostly because he worked—and excelled—in every field. Tireless, creative, and immersive, Girard was most comfortable when absorbed in a project, and he managed to complete a staggering catalog raisonné in his lifetime: houses, department stores, trendy restaurants, less trendy restaurants, logos, a terrazzo material, an airline, a folk art museum, even an imaginary land with its own language. Though to get a real handle on Girard’s output, one must start with the textiles—over 300 unique patterns produced throughout his career—which have come to inform the popular interpretation of his oeuvre.

“His graphics are what people gravitate toward,” says Herman Miller archivist Amy Auscherman. “Even if people don't know who designed them, they respond really strongly.” In fact, Girard ran the first textiles division at Herman Miller, working alongside his friends and collaborators George Nelson and Charles Eames. While much of his work for the furniture manufacturer is considered ahead of its time (passion projects like the Textile & Objects Shop in New York City were only open for a matter of months), Girard’s layered merchandising approach steered the retail landscape for decades to come.

Girard’s colorful, geometric, typography-driven, and folk-inspired personal aesthetic became indistinguishable from the midcentury look still sold by the Michigan-based company. As later brand director for Herman Miller Sam Grawe wrote back in 2008 for Dwell, “colors hitherto considered gauche—magenta, yellow, emerald green, crimson, orange—became a part of the company’s formal vocabulary, and in time, the world’s.”

Anything Girard touched feels juicy, bubbly, and over-the-top, especially in comparison to its restrained, Knoll-esque cousin, corporate modernism. Grawe points out that nostalgia was Victorian in flavor for the midcentury greats. “With Girard,” he says, “it can be sort of overt. He’s a modernist, but a maximalist.”

Girard’s Palio large-repeat upholstery pattern was designed in 1964 for Herman Miller Textile Division and is now available via Maharam. Courtesy: Herman Miller.

Promotional poster for Environmental Enrichment Panels designed by Alexander Girard for Herman Miller, 1972. The selection shows his distinctive range of color, form, and typography. Courtesy: Herman Miller.

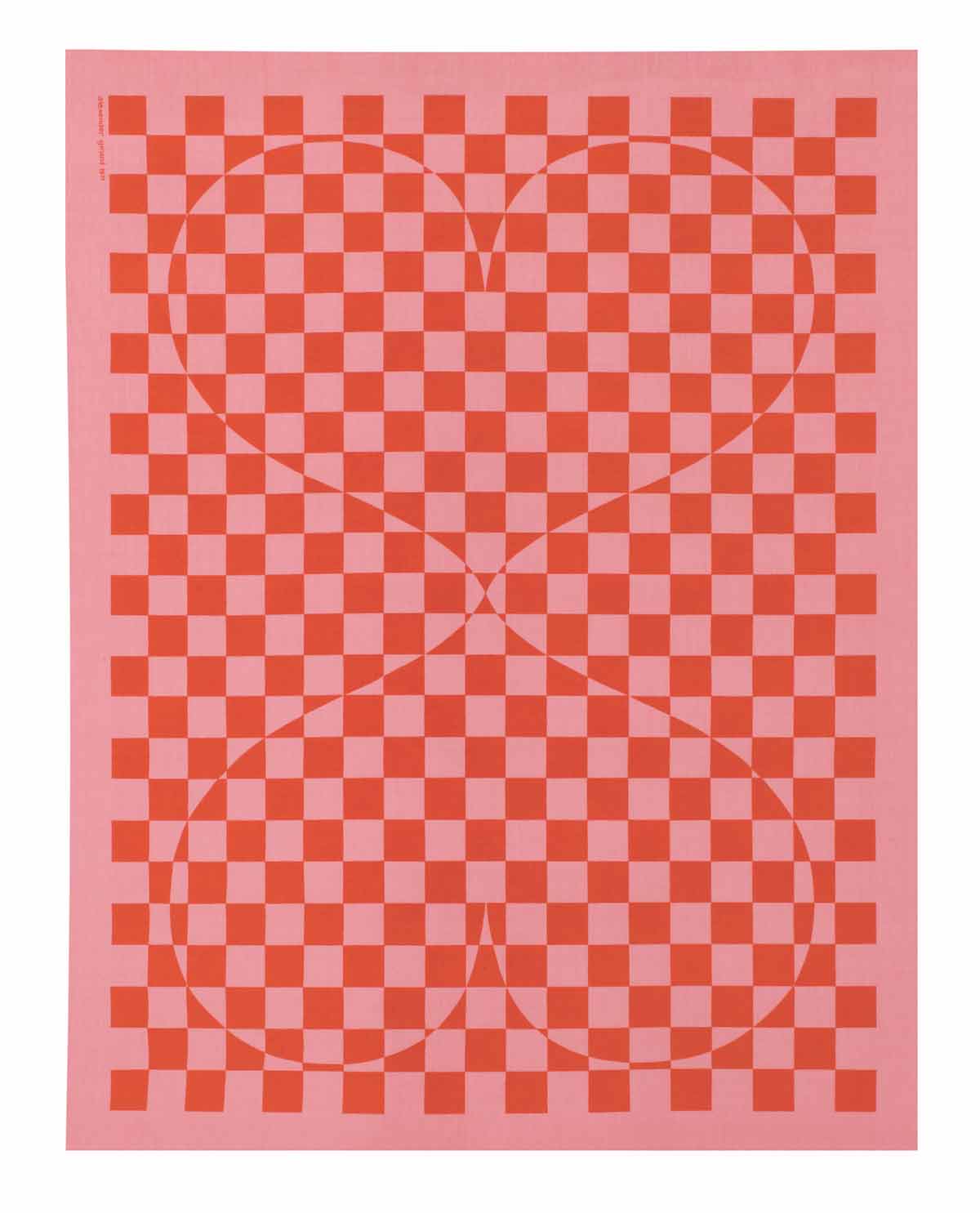

Girard’s granddaughter, Aleishall Girard Maxon, writes for Vitra Magazine, “The symbol itself is composed of two intersecting S’s that form a continuous loop of mirrored hearts, each S representing the first letter of the pet names Girard and his wife had for one another, Sandro and Susie.” Courtesy: Alexander Girard Estate.

Alexander Girard (“Sandro” to friends) is so deeply associated with American design history that it is perhaps surprising to learn of his origin story. He was born in New York City but raised in Florence, Italy. He spoke five languages and trained as an architect in Rome and London. He was dispatched across the continent of Europe to projects in Barcelona, Florence, Stockholm, and Paris. Those peripatetic beginnings directly informed Girard’s legendary fascination with diversity in design objects: a palimpsest of decorative arts history, regional craft, and architecture.

He was also, though shy, not nearly as self-serious as his profession might have prescribed. Jack Lenor Larsen once described him as “Puck, a bright boy with many toys and games to share, magician and fairy godfather.” Even as a self-employed and up-and-coming twentysomething, Girard was unbound by the traditional duties of an architect or interior designer.

A series of personal logos reveals that Girard the designer and Girard the man were indivisible; traces of his personal life are ever-present in his professional work. An early iteration that incorporates a typographic riff on his script handwriting and a simplified Cinderella’s castle of a structure dates to 1934. In 1936, he began using the portmanteau “Sansusi” as shorthand for him and his wife, Susan. The accompanying motif he made to represent their partnership—an entwined double-heart—shows up repeatedly in later textile patterns.

Girard’s work is often concerned with what Monica Obniski refers to as the “larger postwar discourse designed to influence consumption patterns and taste in the home.” The most obvious evidence of this influence over the domestic realm is at the private home of J. Irwin Miller, an industrialist and philanthropist with a profound respect for the impact of design, in Columbus, Ind. (Miller’s company, Cummins Engine Co., hired architects like Kevin Roche and Harry Weese to design its buildings, and Columbus is now home to an annual event promoting architecture in the community.) Miller and his wife Xenia hired Eero Saarinen to design their family house. Girard handled the interiors, and Dan Kiley designed the landscape.

Girard’s contributions to the Miller House include a vanguard feature in the living room, in which he eschewed a formal seating arrangement for something called a conversation pit. Yes, in 1957, Alexander Girard invented the conversation pit, which became a huge fad and spawned generations of imitators. Over the years, he also advised Xenia Miller on everything from what artwork to display on the family’s walls to the patterns that adorned the custom cushions on their Saarinen dining chairs—Xenia’s sewing circle executed Girard’s designs in detailed cross-stitch.

The result of Girard’s endeavors is a masterpiece, and the J. Irwin Miller house remains one of the most important homes ever built in the United States. Since 2011, when the Indianapolis Museum of Art took over the house and opened it to the public, awareness of Girard has increased exponentially.

In his own day, Girard wasn’t much for self-promotion. “He wasn't in it for personal glory,” says Auscherman, who digitized the Miller House collection for IMA. “You can see it now, that he’s not as well-known as the Eameses, or a brand marketer like Nelson. He was doing the work, which is what he cared about.”

Eventually, he was able to retreat into a world of his own design. Girard and his wife (who ran the business side of his creative enterprise) decamped for the last four decades of his life to Santa Fe, New Mexico. There, he was able to create an alternative studio practice dedicated to what he called “aesthetic functionalism.” It is telling that Girard chose to make his home base in the southwest over New York or Los Angeles. It expresses his deep respect for ancient human history, an abiding love of folk art, and the desire to quietly channel his energies into designing complete environments to fit his singular point of view.

“His taste is connected to everything and nothing—it eats everything around it.”—Sam Grawe

It’s fitting, then, that one of the most expressive—and extant—Girard’s works is found in Santa Fe. At the Museum of International Folk Art, the designer’s 10,000-piece collection is on permanent display in a gallery of his own design. Of course, the words “collection” and “gallery” hardly do it justice. “The Girard wing is a synopsis of his various design strategies,” says MoIFA curator Laura Addison. She points out his trademark vertical planes of color that can also be seen in the glazed bricks of a house he designed in Michigan and on the Hemisfair building in San Antonio, Texas. His use of texture shows up in wood paneling in the museum gallery and in murals for John Deere and Albuquerque’s First Unitarian Church. And there’s his signature mix of “high art” (modern design) with “low art” (his collection of crafts, folk art, toys, and figurines) present in just about every Girard project ever.

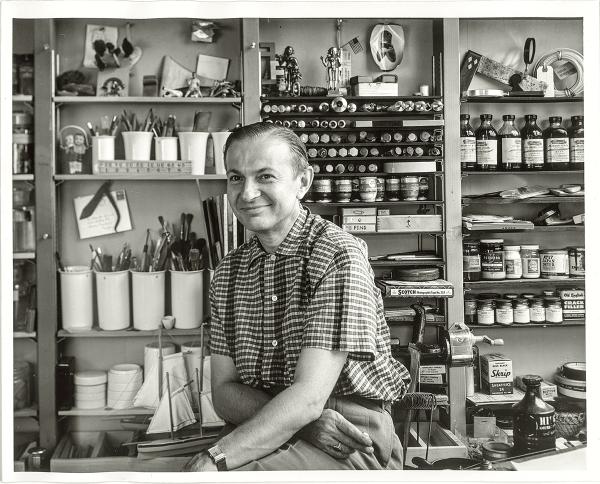

While that approach could read as footloose, Girard was in fact extraordinarily methodical. “It was pretty incredible to witness his studio, the kitchen, the drawers in his bedroom, or his supplies of any kind. Everything was meticulously organized,” says Aleishall Girard Maxon, Girard’s granddaughter. “He was trained as an architect three times over, and that organization—how you think about a building from start to finish—was how he approached every project.”

Maxon and her brother, Alexander Kori Girard, have spearheaded the designer’s legacy; they manage all the family’s licensing and exhibitions through Girard Studio. They note the Washington Street storefront project in Columbus, Indiana, as another example of their grandfather’s vision. It relentlessly and optimistically posits that a designed environment will better engage its inhabitants. As Alexandra Lange writes in her essay for Alexander Girard: A Designer’s Universe:

“He treated the whole town as a composition to be organized, a flat surface over which complex and colorful elements might be gridded and arranged in individual white boxes like his textiles for Herman Miller, or, closer by, his handling of the storage wall in the J. Irwin and Xenia Miller House. The way that Bill Chambers connected Girard’s dismay over the American commercial landscape to the organization of Girard’s own office is entirely apposite: Girard would have arranged and touched up the world, given the chance.”

Girard was undoubtedly a designer concerned with gesamtkunstwerk or “total artwork.” Consider his plan for Washington Street. It wasn’t enough to repaint building facades; instead, working à la Girard meant considering the window seat, the upholstery on the window seat, the window treatments, the view from the window, the view into the other windows, and the window itself.

You can glimpse his inner worlds equally well in the vitrines housing his various collections at MoIFA and in the Republic of Fife—an imaginary country Girard designed as a child at boarding school. All of these demonstrate not just his interest in a great quantity and diversity of projects but his dedication to a staggering array of details within a single work. “He was at every single touchpoint, defining his style on paper and in real life,” explains Auscherman.

One tangible example is the matchbooks he designed for La Fonda Del Sol in 1960. (If you’ve ever been on a late-night eBay binge, hunting for “sun motif” like an Icarus of midcentury aesthetics, then you know the ones.) Along with coordinating sugar-cube packaging, menus, cocktail napkins, and more, the matchbooks have reinforced La Fonda Del Sol’s design as iconic, even though the restaurant itself closed in 1974.

Which means that even though many of his projects no longer exist, the contemporary viewer can still identify with Girard’s point of view. “Girard to me is about living,” says Grawe. “There’s a spirit to his work, and it reminds you of what it is to be a human being.”

Additional Resources

Articles

Ausherman, Amy. “Mid-Centrury Mater Alexander Girard Wins 2019 AIGA Medal.” Why Magazine. Herman Miller.

Glueck, Grace. “Design Review: A Showman Who Turned Interiors Into Atmospheres,” by Grace Glueck, The New York Times, September 15, 2000. https://www.nytimes.com/2000/09/15/arts/design-review-a-showman-who-turned-interiors-into-atmospheres.html?mtrref=undefined.

Grawe, Sam. “Alexander the Great,” by Sam Grawe, Dwell, February 2008.

Williamson, Leslie. “Miller House in Columbus, Indiana by Eero Saarinen,” Dwell. https://www.dwell.com/home/miller-house-in-columbus-indiana-by-eero-saarinen-7565ad76.

Books

Brown, Susan, Jochen Eisenbrand, Barbara Hauss, Alexandra Lange, Monica Obniski, and Jonathan Olivares. Alexander Girard: A Designer's Universe. Edited by Jochen Eisenbrand and Mateo Kries. Vitra Design Museum, 2016.

Coffee, Kiera, and Todd Oldham. Alexander Girard, by Todd Oldham and Kiera Coffee, AMMO Books, 2011.

Herman Miller: A Way of Living. Edited by Amy Auscherman, Sam Grawe, and Leon Ransmeier. New York: Phaidon, 2019.

Exhibitions and events

Alexander Girard: A Designer’s Universe. Museum of International Folk Art, April 29, 2020 to December 31, 2021. Web. 7 May. 2020.

Websites and collections

Maharam. “Alexander Girard.” https://www.maharam.com/collaborators/girard-alexander.

Audio and video

Alexander Girard: A Designer’s Universe. Virtual Tour. Museum of International Folk Art, April 29, 2020 to December 31, 2021. Web. 7 May. 2020.