2021 AIGA Medalist: Cheryl D. Miller

“Expanding Access”

Recognition

2021 AIGA Medal

Born

1952, Washington, D.C.

By Jennifer Rittner

September 8, 2021

Follow Us

Recognized for her outsized influence within the profession to end the marginalization of BIPOC designers through her civil rights activism, industry exposé writing, research rigor, and archival vision.

Cheryl Holmes Miller is a graphic designer—a statement that’s true but not sufficient. Miller is also an advocate and activist. She’s a writer, educator, and researcher; a fighter, a theologian, and a survivor. More than that—Miller is a legacy.

Miller’s legacy is as much the visual impact of her work as it is her forthright critique of an industry that has persistently marginalized Black talent. As a graduate student at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute in 1985, she raised the red flag with her aptly titled thesis, “Transcending the Problems of the Black Graphic Designer to Success in the Marketplace.” That seminal work, subsequently published by Print magazine in 1987 under the headline “Black Designers: Missing in Action,” catalyzed a discourse around diversity and inclusion in the design industry that continues to unfold in conference talks, hiring decisions, statements of purpose, and the makeup of AIGA’s national and chapter leadership. In so doing, she invited the industry to look inward even as she herself moved beyond the practice of graphic design.

Born in Washington, D.C., in 1952, Miller’s childhood was filled with art and design. She grew up in an upper middle-class multiracial family that was deeply embedded in the Black cultural zeitgeist: the Black bourgeoisie of Howard University and the now historic Brookland neighborhood, where she attended Girl Scout meetings at the home of famed Black physician Jack Edward White. Ed Hubbard photographed her as a baby in a home that Miller describes as classic mid-century modern with Danish Krenit bowls on the counters and modern art hanging everywhere. Exposure to art was everything for Miller, who soaked it up and developed her own distinct visual perspective that won her numerous art awards as a child.

Cheryl, dressed here in her Girl Scout uniform, receives an art award, news of which was printed in the Washington Post on December 16, 1962.

Cheryl with her parents in a photo taken by Ed Hubbard at his home in 1955.

Miller’s studio portrait taken by Ed Eckstein in 1988.

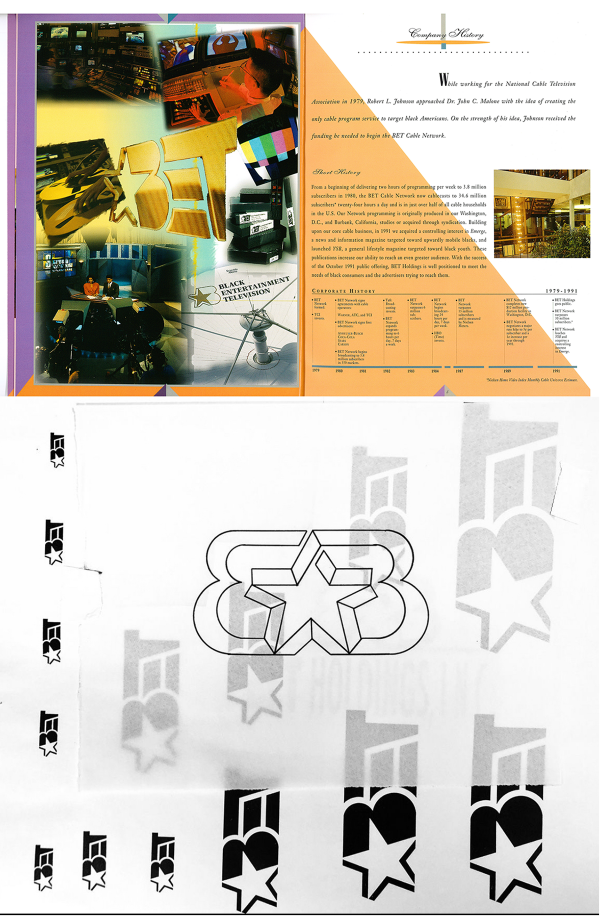

The 1992 BET Holdings Inc. first annual report (top). Miller’s logo sketch design for the new holding company (bottom).

Press Release

Cheryl D. Miller will be honored with the AIGA Medal during the AIGA Awards Celebration at the AIGA Design Conference on Tuesday, September 21, 2021 at 5:30 p.m. Eastern. Come celebrate with us!

When the time came to consider a path, Miller found herself presented with a binary choice: writing or art (it turned out to be a false distinction since Miller ultimately distinguished herself as an artist-author). She opted for art first, attending the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 1970. She was a Freshman when her father became terminally ill. Upon his death, Miller returned to D.C. to complete her BFA at Maryland Institute College of Art. During her time in art school, she began to formulate her thoughts on Black marginalization in the academy, marking the beginning of an inquiry that would develop throughout her academic career and professional practice.

Miller found success in the struggle. In 1984, she moved with her husband to New York City where she founded her design firm, Cheryl D. Miller Design Inc.—one of the first Black women–owned firms. There, she designed corporate communications for Fortune 500 clients, including BET, Chase, American Express, Time Incorporated, Sports Illustrated, Philip Morris, and McDonald’s; as well as for non-profit clients who aligned with her dedication to personal activism and the social movements of the era. Among these were the United Negro College Fund, the National Urban League, the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, and the Jackie Robinson Foundation, many of which had arisen out of the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Her client work, coupled with her studies at Pratt Institute, where she earned an MS in Communications Design, catalyzed for her the collision between her childhood experiences of access and exposure against a world in which the racial politics of exclusion came to define what success might look like for her and other Black designers. It was this revelation that birthed her thesis essay on the condition of racial segregation in the design industry.

The publication of her 1987 essay brought attention and opportunity. Reflecting on the serendipities of her life, Miller acknowledged that she “hit the wave at a time of advocacy.” In the 1980s, advertising peers at the vanguard of Black design and advertising, included, Tom Burrell, Caroline Jones, and others who collectively defined what it meant to be Black, to design Black, to advertise Black, and to build a Black visual landscape.

Harlem Week. Corporate communications for Chase Manhattan Bank in 1985. Illustrator Yvonne Buchanan.

Transcending the Problems of the Black Graphic Designer to Success in the Marketplace (Thesis). Miller’s 1985 thesis paper and the subsequent publication in Print Magazine catalyzed a conversation about segregation in the design profession.

“Black Designers Missing in Action” (Article). Miller’s 1985 thesis paper and the subsequent publication in Print Magazine catalyzed a conversation about segregation in the design profession.

Logosheet of Miller’s hand drawn logos, 1974–1994.

Miller’s firm excelled at social impact corporate communications, which reflected the growing awareness in the 1980s and 1990s that companies could be both profitable and responsible. Her work with those clients was both professional and deeply personal, in some cases changing her life’s path. For example, a project for Union Theological Seminary led her to pursue a Master of Divinity and her ordination as a Christian minister.

For Miller, design is communication, communication is a form of activism, and to be an activist is to be a preacher at heart; someone who excites the spirit and activates the good work that heals and uplifts communities. “Her commentary on the necessity of inclusion and the plight of Black designers sang like trumpets in my mind,” says David Jon Walker, associate professor of art in graphic design at Austin Peay State University. “It alerted me to the fact that I was not alone in my familial, educational, and career experiences, and that brave trailblazers had begun the work that I was faithfully choosing to traverse.”

For all of the successes that marked Miller’s career throughout the 1980s and ’90s, she laments the many lost opportunities — high-profile projects that renowned white designers won but that might have changed the course of many careers had they been awarded to Black designers. Miller chafed against the limitations placed on her and her colleagues — the long, persistent shadow of Jim Crow politics that poisoned all facets of American culture — and questioned the inequities of how “design excellence” was defined, perceived, and rewarded. She does not hide her disappointment at how celebrated white designers were given the opportunity to create iconic album covers and music posters featuring some of the greatest Black artists and musicians of the time. Disappointment turned to insult as she considered the many Black designers who should have gotten that call and would have benefitted from the exposure, but more importantly would have had something particularly Black to express in their work. Instead, she watched as white designers created that work, rose in the industry, and took home awards.

For Miller, these moments tell the story of an industry that continuously neglected to support and elevate the contributions of Black designers. If you ask, she will read you chapter and verse and, yes, she will name names, about how she felt overlooked and undermined in her prime. It was the indignity, erasure, and minimization of the Black designer that fueled her activism and honed her critique of the industry.

The Congressional Black Caucus Foundation Inc. Hand-drawn logos and letterhead inspired by Aaron Douglas.

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (Cover). Annual Report 1988–1989. Photographer John Pinderhughes.

The United Negro College Fund and American Business (Cover). Corporate communications designed to leverage quality duotone printing and high impact photography. Photographer Ed Eckstein.

Illustration by Charles Lilly, Miller’s poster design was commissioned by NASA to honor astronaut Dr. Mae C. Jemison.

In the late 1990s, Miller placed her business on hiatus to focus on parenting, which led to new opportunities, including teaching, preaching, and focusing on fine art. And while she has never ceased to be a designer, her most profound impact these last two decades has been as a mentor and cultural critic. “Cheryl is the industry mentor I never imagined I'd have,” says Kaleena Sales, the chair and assistant professor of Tennessee State University’s graphic design department. “I'm motivated by her robust research, writing, and genuine desire to make a positive impact in this industry. Mostly, I'm inspired by her honesty. She is a trailblazer, and someone who is undoubtedly paving the way for the next generation to follow.”

Since the beginning of her career, Miller built and maintained a comprehensive archive of the work she created under Cheryl D. Miller Design Inc. In 2018, Stanford Libraries acquired the extensive archive of her personal and professional work for The Cheryl D. Miller Collection at Stanford University. Currently, Miller is working with Stanford Libraries and various design colleagues to curate the open source database The History of Black Graphic Design in North America.

Miller’s design work can be read in the context of graphic design history, but is best understood in the context of broader sociopolitical dynamics. She often encourages people to look at the timeline of history to engage in a more honest discourse around how the graphic design industry intersects with the social movements of each era. Miller believes it’s intersections, collisions, and often negations that inform the narrative of the graphic design industry. “Cheryl's work and her viewpoints have had an immense impact not just on how I think about Revision Path, but also in how I can continue the conversation about the presence of Black designers in this industry,” says Maurice Cherry, creator of the podcast Revision Path. “We should all be thankful not just for her recollections of the past, but also for the wisdom she imparts about where we should go for the future.”

Miller continues to write, teach, and build an archive of Black design history. Following her groundbreaking graduate thesis, she wrote the 1990 essay “Embracing Cultural Diversity in Design.” In 2013, she published her memoir, Black Coral: A Daughter’s Apology to her Asian Island Mother. In 2016, she updated her original Print article with the piece, “Black Designers: Still Missing in Action?” and continued the narrative in 2020 with “Black Designers: Forward In Action,” which explores the history of the Black designer and showcases the considerable cadre of Black designers across the United States.

In February 2021, Miller was awarded the Doctor of Humane Letters from Vermont College of Fine Arts. And in recent years, Miller has held positions as designer in residence, and is currently a distinguished senior lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin School of Design and Creative Technologies; Doty Fellowship recipient. She has been an adjunct professor at Roger Williams University and is a Maryland Institute College of Art 2021 William O. Steinmetz designer in residence. She was an adjunct faculty member at Lesley University’s College of Art and Design and is currently an adjunct professor at Howard University.

As Miller continues her dedication to decolonizing graphic design pedagogies and practices, a new generation of Black and BIPOC graphic designers are bringing their voices to bear, many of whom claim Miller as their guide. When asked about her legacy, Miller joyfully states that it comes down to a mantra she’s lived since the early days of her career: “Success is when opportunity meets the prepared.” Miller continues to define success by advocating, teaching, and sharing stories of graphic design history while leading a path forward for diversity and inclusion.

Sources

Interviews with Cheryl Holmes Miller, May 25, 2021 and June 17, 2021.

Miller, Cheryl D. “Transcending the Problems of the Black Graphic Designer to Success in the Marketplace,” Master of Science Thesis, Pratt Institute, NY: May 1985.

Miller, Cheryl D. “Black Designers: Missing in Action,” Print Magazine, Sept/Oct 1987.

Miller, Cheryl D. “Black Designers: Still Missing in Action?” Print Magazine, Summer 2016.

Miller, Cheryl D. “Black Designers Missing in Action” (video). Poster House, May 24, 2020 . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mYD0IWp0_A

Hayes, Dorothy, An Exhibition by Black Artists. Communication Arts: November 2, 1970 (Vol 12, No 2).

MICA Graphic Design Archives, Cheryl D Miller Steinmetz Designer in Residence collection, https://micagdarchives.com/Cheryl-D-Miller-Steinmetz-Designer-in-Residence

Orton, Kathy, “Brookland home is tied to mentors in medicine and architecture,” The Washington Post, December 7, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2018/12/07/brookland-house-is-tied-mentors-medicine-architecture

Roberts, Regina. “Press Releases | Meet AIGA's Awards Recipients, representing the vibrant spectrum of design excellence | AIGA,” www.aiga.org. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

Shashkevich, Alex. “Knight Fellow’s project leads to a new collection at Stanford Libraries,” Stanford University News, July 11, 2018. https://news.stanford.edu/2018/07/11/one-question-led-new-stanford-archive