2021 AIGA Medalist: Thomas Miller

“Expanding Recognition”

Recognition

2021 AIGA Medal

Born

1920, Bristol, Virginia

Deceased

2012, Chicago, Illinois

By Chris Dingwall

August 2, 2021

Follow Us

Recognized for his tenacity and impeccable craft as a pioneering graphic designer and art director for global brands—based in Chicago, whose work culminated in the timeless DuSable Museum mosaics.

Thomas H. E. Miller was among the pioneers of African American designers celebrated at the DuSable Museum of African American History in Chicago in 2000. To a full auditorium, he recounted his career with an efficiency and focus that also characterized his work as one of the leading graphic artists of his time: “I came out of World War II. . . . and went in the [art] school under the GI Bill and was promised a job the minute I came out—of which I didn’t get. So I was one of the few people who graduated from that school who didn’t get a job and that was mainly because I was Black. But that didn’t stop me, obviously. Eventually . . . I got a job with Mort Goldsholl and I stayed with him 33 or 35 years, and retired from there.”

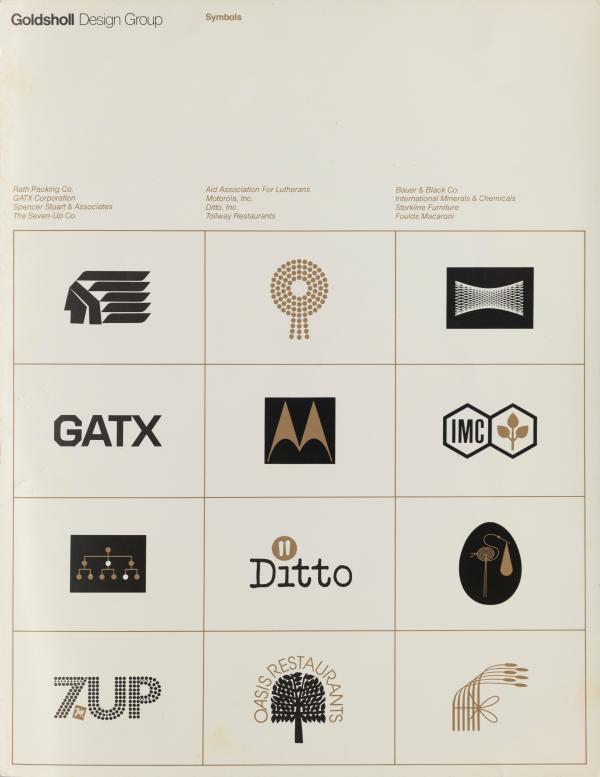

During his tenure at Goldsholl Associates, Miller helped design some of the most iconic corporate brands of the twentieth century: Motorola, the Peace Corps, Bauer & Black, and 7Up, among many others. In the non-hierarchical Goldsholl studio, Miller worked on not only logo design but also packaging, stop-motion and video animation, and exhibition displays. An enthusiastic tinkerer and a lover of gadgets, movies, and cartoons, he experimented with many techniques that are now staples of video production and digital graphics. It is no exaggeration to say that his work helped to reshape not only several fields of design practice but also the sensory experience of our consumer society. Miller’s career was revolutionary, his achievements as a designer matched by his achievements as a citizen who successfully challenged racism in the American design professions.

Thomas Miller, “Dr. Margaret T. G. Burroughs,” 1995. DuSable Museum of African American History, Chicago. Photograph: Chris Dingwall.

7Up Cans (green and red) from the collection of Tim Samuelson. Photograph: James Prinz Photography, Chicago.

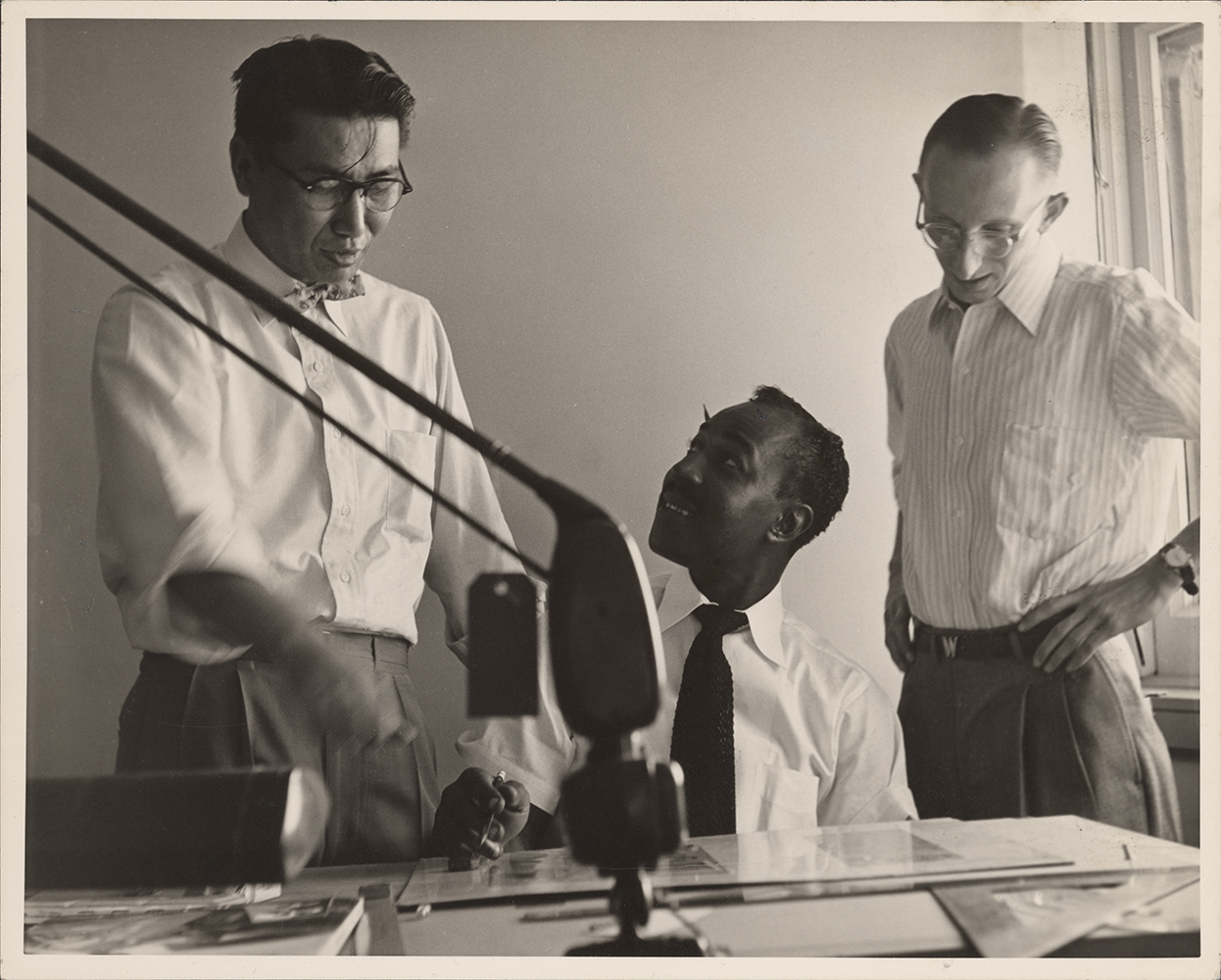

Photograph of Fred Ota, Tom Miller, John Weber, 1953. Thomas H. E. Miller Design Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Press Release

Joyce Miller-Bean accepted the AIGA Medal for Thomas Miller during the AIGA Awards Celebration at the AIGA Design Conference on Tuesday, September 21, 2021 at 5:30 p.m. Eastern. Thank you for celebrating with us!

Miller was born in Bristol, Virginia, in 1920, a time when the Ku Klux Klan marched openly in the street and African Americans received the lesser end of the city’s segregated public services. His father, a railroad brakeman, was killed on the job when Miller was a child. His mother was a domestic worker whose work ethic deeply impressed her son. Although Bristol’s segregated schools allotted few artistic resources for Black students, Miller was undeterred from pursuing his creative vision. “Nothing hampered me from doing artwork,” he told journalist Lauren Fitzpatrick during an interview in 2007. “I lettered in football. I lettered in basketball and track, but I’d always go back to doing art.” At the historically Black Virginia State College (now Virginia State University), he earned a bachelor’s degree in education with an emphasis on art before enlisting in the (still-segregated) army. Deployed across Europe to fight the Nazis, Miller eked out time and resources to paint. Befriending a sympathetic supply sergeant, he obtained watercolors and oils and constructed canvases out of surplus army cots; reportedly, he even sold a few landscapes during this three-year tour.

After the war, Miller immediately began his own quest for equal rights in the field of professional design. Although returning African Americans soldiers did not receive equal treatment from the U.S. government, Miller was able to take advantage of the GI Bill that allowed veterans to gain college education or vocational training. Miller enrolled in the Ray-Vogue School of Art in Chicago and, in 1950, earned a specialized degree in commercial and graphic art. At the Ray-Vogue School, Miller was the only Black student, which drove him to go above and beyond during his studies, learning techniques such as airbrushing and retouching that were needed for commercial art. “I had to be super-qualified,” he told Fitzpatrick. “I took things in art that weren’t necessary, like airbrushing and retouching and things you didn’t have to do because I wanted to be prepared in case someone would ask me to. They couldn’t use that as an excuse for me being not qualified.” In the design profession, he discovered another rigid color line: a racism more genteel than a Klan march but no less degrading for the young professional. The Ray-Vogue School, for instance, limited the number of Black students who could enroll. On the job market, Miller experienced racism in moments that could have come from the pages of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. “You’re very talented,” one prospective employer told Miller. “Too bad you are so dark.” Another suggested he could work but only behind a screen, out of sight from clients.

Goldsholl Design Group, Symbols, c. 1975. Thomas H. E. Miller Design Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago.

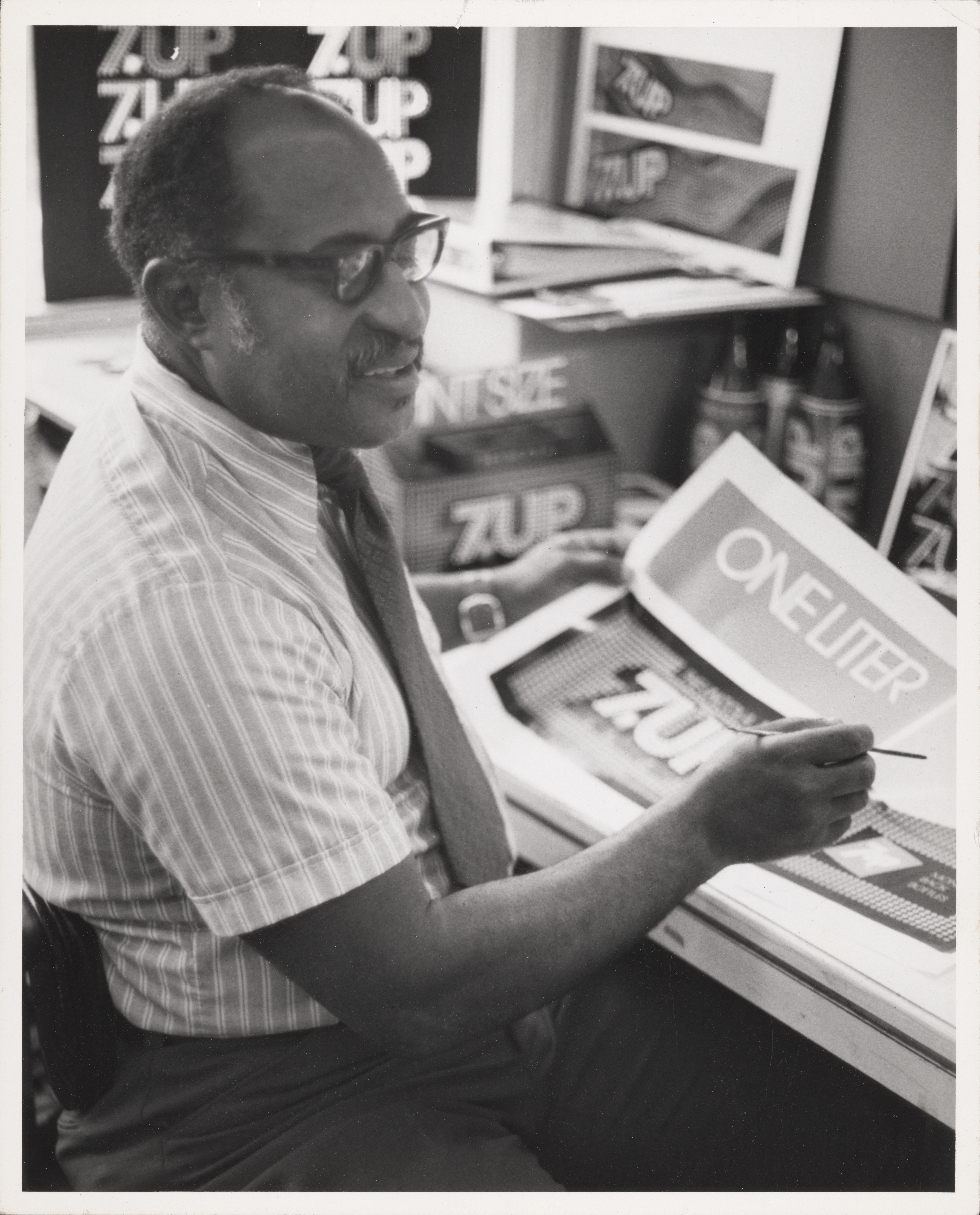

7Up Contact Sheet, 1975. Thomas H. E. Miller Design Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Thomas Miller, “Harold Washington,” 1995. DuSable Museum of African American History, Chicago. Photograph: Chris Dingwall.

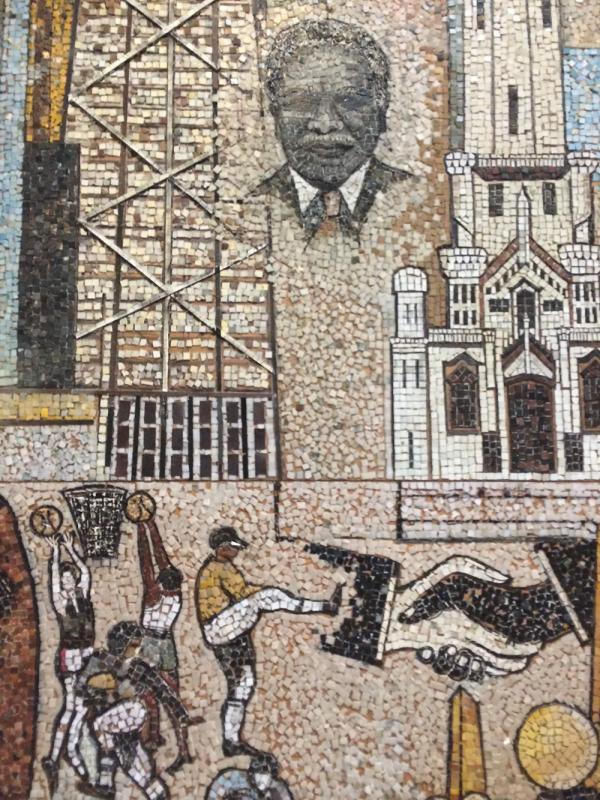

Thomas Miller, Detail from the DuSable mosaics, 1995. DuSable Museum of African American History, Chicago. Photograph: Chris Dingwall.

Miller would find a home at the Goldsholl Associates. He was among the first designers hired by Morton and Millie Goldsholl when they formed their own studio in 1955. Graduates of Chicago’s School of Design and students of Hungarian émigré László Moholy-Nagy, the Goldsholls were for Miller a living connection to the vanguard of modern design. With the Goldsholls, Miller participated in the reconstruction of one corner of the design industry. The Jewish American Goldsholls would not only espouse Moholy-Nagy’s socially egalitarian design philosophy but also sought to re-create its egalitarian workplace where white Americans, African Americans, Japanese Americans—and men and women—worked together as equals. Miller’s daughter, Joyce Miller-Bean, remembered the Goldsholl studio as an “international family.” Co-workers were welcome friends at the Millers’ home in Morgan Park, and the Millers were frequent guests at the Goldsholls’ Highland Park home. In many respects, Miller’s cosmopolitan career and social life was a model for what was then called America’s Second Reconstruction: the Civil Rights Movement that during Miller’s career daringly challenged the white power structures that segregated both the Jim Crow South and the putatively liberal professions in the North.

For Miller, the reconstruction of the world extended to the aesthetics of design itself. Working the Motorola account in 1955, Miller particularly admired how the team rendered the “M” as an oscilloscope wavelength, an abstraction that distilled the complexity of the communications industry into its most essential form. Miller applied these principles to the 7Up redesign in 1975. Launched in 1929, 7Up was first marketed as a tonic for an ailing stomach. By the 1950s, advertisements were hokey: model consumers drinking 7Up at picnics, in living rooms, soda shops, and other spaces of bourgeois life. Miller overhauled the brand almost entirely. Like the Motorola “M,” Goldsholl's “see the light” campaign elevated the commodity—citrus-flavored carbonated sugar water—to a higher essence: the effervescent bubbles as dots of light. Rather than address a particular “White” or “Black” market, Miller’s redesign envisioned the consumer marketplace on the most universal and egalitarian terms: as a drink for everyone, in any place at any time, in a graphic style far more sophisticated than the contemporaneous “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” campaign. The new 7Up appeared everywhere, on bottles and cans, in magazines and store displays, and won Miller awards and professional recognition.

Miller’s commitment to the egalitarian ideals of the Civil Rights Movement and of modern design were lifelong. When Miller retired from Goldsholl, he returned to art and to civil rights activism. In the late 1980s, the NAACP commissioned Miller to produce a plaque honoring the accomplishments of Harold Washington, Chicago’s first Black mayor, who had been elected in 1983 and died suddenly during his second term in 1987. Washington’s election greatly impressed Miller. When artist Margaret Burroughs commissioned him to design the murals for the DuSable Museum, which were installed in the museum lobby in 1995, he made the mayor a central figure, his portrait framed by Chicago’s iconic Water Tower and the Hancock skyscraper along with emblems of interracial comity. The mural was not only an expression of Miller’s politics but also a consummation of his design career. Miller built his mosaics out of translucent plastic squares made from egg crate light diffusers, the mesh squares that filter light from overhead fluorescent bulbs common in late-twentieth-century workplaces. Harkening back to his army days, Miller sourced the material from offices around the city and broke them down with the help of his children. He handpainted each tile—thousands of them—and assembled them into a pre-planned grid. At once homespun and carefully executed, Miller’s mosaics refracted the “light” of his 7Up campaign to envision a reconstructed Chicago. Each tile had to be placed at a precise angle, he explained, “to catch the light.”

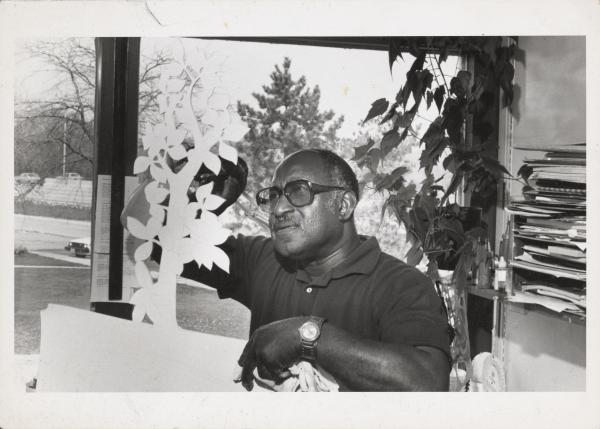

Hero image

Thomas Miller at Goldsholl Associates, 1975. Thomas H. E. Miller Design Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Sources

Lauren Fitzpatrick, “Life by Design: After career overcoming racial obstacles, top graphic artist finds new creative outlet,” Southtown Star, Feb. 18, 2007. Online: https://terminationdate.wordpress.com/by-lauren-fitzpatrick/2007-southtowners-life-by-design/ (Accessed May 25, 2021)

Thomas H. E. Miller in “A Conversation with the Pioneers,” interview conducted by Victor Margolin for African American Designers: The Chicago Experience Then and Now at the Du Sable Museum of African American History, Chicago, February 5, 2000. Recorded by Video One Productions, Feb. 5, 2000. Online: https://youtu.be/jhq3YQiIEtM?t=870 (accessed June 18, 2021).

Victor Margolin, “African American Designers: Some Preliminary Findings,” unpublished mss. (c. 2000). Online: https://victor.people.uic.edu/articles/blackdesigners.pdf (accessed June 18, 2021)